People's Socialist Republic of Albania

| People's Republic of Albania (1946–1976) Republika Popullore e Shqipërisë People's Socialist Republic of Albania (1976–1991) Republika Popullore Socialiste e Shqipërisë | |

|---|---|

| 1946–1991 | |

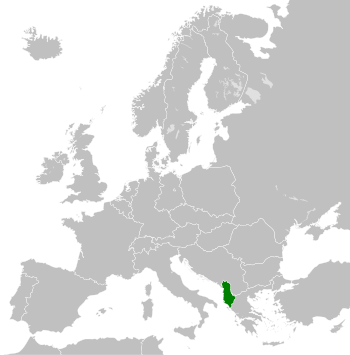

The People's Socialist Republic of Albania in 1976. | |

| Capital and largest city |

Tirana |

| Mode of production | Capitalism |

| Government |

Unitary people's democratic Marxist–Leninist republic (1946–195X) Dictatorship of the Bourgeoisie (after 195X) |

• First Secretary |

Enver Hoxha (1946–1985) Ramiz Alia (1985–1992) |

The People's Socialist Republic of Albania (PSRA),[a] known as the People's Republic of Albania prior to 1976 or simply the PSRA, was a state which existed from 1946 to 1991. It was led by the Party of Labor of Albania, whose first secretary was Enver Hoxha. Hoxha would go on to betray the proletarian dictatorship by supporting Khrushchev in the Secret Speech and the following ousting of the so-called Anti-Party Group. [1] [2] After Hoxha's death in 1985, revisionist Ramiz Alia gained leadership. The PSRA would be replaced by the modern Republic of Albania following this counter-revolution.[3]

During the era of Albanian history, the standard of living improved in many ways. Albania's infrastructure was built, literacy rates increased from 5% to more than 90%, epidemics were eliminated, the country was completely electrified, the life expectancy increased by a large degree.[4][5]

History

Prior to the PSRA, Albania was Europe’s poorest nation. The country had not even undergone a widespread industrial revolution; it was an entirely feudal and agrarian nation. After the Italian fascist invasion and occupation of Albania in 1939, a popular national liberation movement arose to resist the invaders, primarily led by communists. The Communist Party of Albania[b] would assume a leading role in this liberation war after its founding in 1941. In 1944, the people's democratic revolution succeeded and a provisional government was established. On 10 January 1946, the People's Republic of Albania was proclaimed.[6]

The post-war economy was devastated. The only fragments of industry were those which had been left behind by the anti-communist occupiers during the national liberation war, a war which damaged their economy even further. The communists swiftly set about transforming the nation’s economy when they came to power in the mid-1940s, nationalizing the remaining industries, enacting land reform programs, and organizing a planned economy influenced by the Soviet Union. By 1951 the socialist state successfully replaced all the existing market forms and mechanisms, and from then on the centralization of the economy intensified:

Based on the experience of the Soviet Union, the Albanian Communist Government introduced a centrally-planned economic system. By 1951, the government replaced all the existing market forms and mechanisms by central planning. From then on the centralization of the economy was intensified. The planning system was based on Five Year Plans, where all the economic decisions on production, pricing, wages, investments, external and internal trade were made at the beginning of the plan, and remained unchanged for the whole period. Changes between the plans were also minimal in terms of wages and prices.

— University of London, [7]

This resulted in impressive economic growth, as well as the rapid development of industry:

During the first period [1945–1975], the Albanian economy was relatively successful. It grew substantially until the break with China in the seventies. The growth of the Net Material Product from one five-year plan to the next was, on average, nearly 44 percent, with industry recording the fastest growth rates during this period. The average growth of industry from 1951 to 1975 was 82.5 percent. The share of agriculture declined from 80 percent during the first five-year plan (1951–55) to 36% in the fifth plan (1971–75), while the corresponding figures for industry were 14 percent and 35 percent, respectively.

— University of London, [7]

Albania played an important role in the Greek Civil War, with many of the guerrillas using Albania for sanctuary, to the extent that it was briefly feared at the time that the Greek government (which also claimed southern Albania as Greek territory and proclaimed itself in a "state of war" with Albania since 1940) would invade. The Soviets did intervene actively in the civil war insofar as they helped supply weapons to the insurgents and helped coordinate all sorts of aid from the People's Democracies.

From 1949 to 1953, Western imperialist states parachuted disgruntled Albanians into the People's Republic in order to overthrow the government, but their schemes failed.[8]

Politics

Albania was first organized as a dictatorship of the proletariat under the leadership of the Party of Labor of Albania. The Party of Labor maintained the Democratic Front of Albania, which united all mass organizations under it. The party was responsible for carrying out the Party's cultural and social programs to the masses, and was in charge of nominating candidates in elections.

Under the leadership of Enver Hoxha, the Albanian state would become Revisionist during the 50's, and betray socialism. [1][2]

Albania's pioneer movement

Albania had its own pioneer organization, the Pioneers of Enver, which was structured similarly to that of the USSR's.

Geopolitical Vaccilation

The Albanian government vacillated heavily on Geo-political affairs. Albania remained loyal to the Soviet Union long after the USSR had become revisionist, up till 1960. Albania would then remain loyal to the Chinese Communist Party and Mao Zedong until the Sino-Albanian split completed around 1978. In those times Hoxha praised Mao, and his theoretical works, including the application of the cultural revolution as described by Mao Zedong and Lin Piao. [9]

Economy

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

In 1969 the PSRA abolished direct taxation,[10] and during this period they continued to improve the quality of schooling and healthcare. It was during this period that the PSRA achieved full electrification, becoming one of the first nations on Earth (possibly the first, according to some sources) to do so. The socialists brought electricity to every rural district in the republic (the vast majority of the population was rural), and they gave cities full power as well.

Labor unions and cooperatives were structured similar to those of the USSR, the most noteworthy difference being that starting in 1971, Albania introduced a number of "higher-type cooperatives" (HTCs), a transitional form between collective farms and the state farms (e.g. members are paid wages like on state farms). The Party of Labor performed a rather unique experiment in the field of agriculture with these:

In 1971, however, a new form of agricultural cooperative was established as a means of faciliating the transformation of all cooperatives into state farms … The first 'higher-type agricultural cooperative' (HTC) was inaugurated in that year, and was given exclusive access to one MTS, thereby creating an agricultural unit which was intermediate between the typical cooperative farm, which shares an MTS's equipment with other cooperatives, and the state farm, which owns its own machinery. Moreover, methods of payment to the members of HTCs were made to resemble those of state farms more closely than those of other cooperatives in that ninety percent of the planned salary is paid during the year, with the remaining ten percent being paid at the end, if the plan is fulfilled … each member of the cooperative is guaranteed a minimum wage …

In addition to the HTCs, it has been claimed that Albanian agriculture has also made two other unique contributions to Marxist-Leninist theory. Firstly, previously scattered, privately-owned livestock has been brought together into joint herds, and, secondly, the extinguishing of the personal plot, in the wake of the transition to complete state farming, has been explicitly adopted as an aim of policy. . . it is argued that personal plots are incompatible with social ownership, and that in any case the farmer can now buy products at prices in the cooperative shop which are lower than the cost of growing them on his plot.[11]

Infrastructure

It was not just that the industry that experienced rapid growth, infrastructure was also developed. The country’s highway system was greatly expanded, and by 1985 consisted of 6,900 kilometres of roads capable of carrying motor vehicle traffic, and with a small rail network of about 603 kilometres. Within industry, the mineral sector and the electricity generation were initially developed. During 1956-60, the production of chrome made great strides, giving Albania first place in the world in per capita production of chrome ore, and later in the eighties the third place in the world for total output. Because of the large number of rivers and their mountainous nature, Albania developed its hydro-electric potential HEP, estimated at 2500 MW, second to Norway within Europe. Thus, in the eighties Albania reached agreement with neighboring countries (Yugoslavia and Greece) to supply them with electricity.

— University of London, [7]

Health

After WWII, Albanian healthcare’s situation was rather desperate:

As explained earlier in this Chapter, when the communists took over in Albania in 1945, the state of the population's health and the Albanian health system were in a very bad state. Before the War, the health system consisted only of 10 state hospitals and an Institute of Hygiene founded in Tirana in 1938. The number of doctors was very low - only 102 Albanian doctors and a very small number of foreign doctors. Thus, the number of physicians (doctors and dentists) per 10,000 of the population was only 1.17, while the number of beds for 1,000 of population only 0.98.

— University of London, [7]

Life expectancy and mortality were among the worst in the world:

According to the League of Nations in 1941, the crude death rate for Albania in 1938 was 17.7 per thousand. In a later study a figure on life expectancy at birth is given for 1938 as 38 years. Even these figures are thought not to be accurate, because death registration was not complete. There was no death certificate form, the posting of registers was always in arrears, and very little information on cause of death was recorded. The majority of villagers died without any medical intervention. In the early twenties over half of the country's 2,540 villages had never been visited by a doctor.

— University of London, [7]

Due to this, the PSRA made healthcare a top priority:

In order to address this situation, the government starting in 1947, introduced a wide-ranging social insurance and medical scheme. Most medical treatments (thought not the medicines) were provided free. Legislation was introduced to protect the mother and child, and set up the pension scheme, as well as other regulations on sanitary conditions and control, and for the treatment of infectious diseases.

— University of London, [7]

As a result of the PSRA’s healthcare policy, Albanian life expectancy increased rapidly:

Most of the improvement in life expectancy at birth occurred in the first decade, when life expectancy at birth increased by 10.4 years for both sexes, more than one year for each year of the decade. In the next three decades mortality continued to improve, although not at the same pace as in the first decade.

— University of London, [7]

The following table charts Albanian life expectancy from 1950–1990, as given by the aforementioned study:

| Years | Life Expectancy (All Genders) |

|---|---|

| 1938 | ∼38 |

| 1950 | 51.6 |

| 1954–55 | 55.0 |

| 1960 | 62.0 |

| 1964–65 | 64.1 |

| 1969 | 66.5 |

| 1975–76 | 67.0 |

| 1979 | 68.0 |

| 1989 | 70.7 |

From these statistics, it is clear that the PSRA achieved an enormous increase in life expectancy, from 38 years in 1938, to 68 years in 1979, an increase of thirty years in just four decades. It continued to improve until 1989, albeit more slowly. The PSRA also succeeded in eliminating various infectious diseases which had plagued the country, particularly malaria, which had been the biggest killer in antebellum Albania:

A number of endemic diseases were brought under control, including malaria, tuberculosis and syphilis. […] If one looks at the mortality transition from 1950 to 1990, it is clear that the pattern changes as life expectancy improves. Thus, the infectious and parasitic (tuberculosis included) diseases decline and almost disappear in the seventies and eighties.

— University of London, [7]

Social security

Social Insurance was first introduced by the Albanian communist government in 1947. The initial social security scheme covered approximately 75,000 people. The social insurance program was administered by state organisations and covered medical care, compensation for disability, old-age pensions, family allowances, and rest and recreation. Several modifications were made latter to the basic program. The law of 1953 provided a program closely resembling that of the Soviet Union, i.e. a classic cradle-to-grave system of social security. For a number of years trade unions administered a large number of social insurance activities. In 1965 the state took over the administration of all phases except those for rest and recreation facilities.

— University of London, [7]

Maternity leave and disability insurance were provided:

If people lost their capacity to work totally or partially, they were granted invalidity pensions. The amount of the pension varied between 40-85% of the wage depending on the scale of invalidity, cause of invalidity and the number of years that the person had been working. Pregnant women were given eighty-four days leave under normal circumstances and were paid at 95% of their wage if they had worked for more than five years and 75% if they had worked less than five. The pregnancy leave period was extended to six months in 1981. Workers could stay at home for limited periods to care for the sick and during this period received 60% of their pay.

— University of London, [7]

Old-age pensions were also provided to all retired workers:

Old-age pensions were based on age and years of work. Payments were calculated at the rate of 70% of the worker’s average monthly wage. Two exceptions were the veterans of the Second World War and the Party leaders who received an additional 10%. The law also provided for widow’s and orphan’s pensions.

— University of London, [7]

All workers were guaranteed time off from work, with pay:

All insured persons were entitled to a paid vacation. The duration of the vacation depended on the type of work and the length of active employment.

— University of London, [7]

Childcare insurance was also an aspect of the social security system:

When children under seven years of age were ill, one of the parents was permitted up to ten days leave during a three month period. A one-time payment was made to the family for each child that was born. In case of death a fixed sum was paid to the family for funeral expenses.

— University of London, [7]

Eventually, the system was expanded to include peasants in farming cooperatives:

From 1st July 1972 the system of pensions and social security was extended to cover peasants working in agriculture cooperatives. This aimed at the narrowing of the differences between urban and rural areas. Some agricultural cooperatives had already introduced some forms of pensions and social insurance providing help for their members in old age and when they were unable to work. The financing of this social security system in the rural areas came from the contributions of the cooperatives with some subsidization from the state.

— University of London, [7]

The provision of a cradle-to-grave social welfare system is an enormous achievement, and one of the main advances made by the PSRA.

Education

The end of the second World War found Albania in a very poor educational state. At that time 80% of the population was illiterate, and in the rural areas this figure reached 90-95%. Illiteracy was widespread in rural areas and in particular among women. Immediately upon seizure of power in 1944, the communist regime gave high priority to opening schools and organizing the whole educational system along communist lines. An intensive campaign against illiteracy started immediately.

— University of London, [7]

This resulted in enormous improvements in the educational system:

In terms of enrollments, Albania had a broad-based education system, with almost 90% of the pupils completing the compulsory basic 8-year school and 74% of them continuing into secondary school. From these, more than 40% went to the university. According to official figures, at the end of 1972 there were 700,000 schoolchildren and university students, which meant that every third citizen was enrolled in some kind of educational institution. The number of kindergartens in urban areas increased by 112% from 1970 to 1990, while in rural areas it increased by 150%. The number of primary schools in urban areas, for the same period of time, rose 31%, and in rural areas 24%. The total number of secondary schools increased by 291%, and that of high schools by 60%. A similar trend is seen for the number of students that graduated. Thus the number of pupils that graduated from primary schools for the period 1970-1990 increased by 74.8%, for the secondary school, the number rose 914.2%, and for university 147%. Education tuition was free of charge. Students whose families had low incomes were entitled to scholarships, which gave them free accommodation, food, etc.

— University of London, [7]

As a result, illiteracy was virtually wiped out across the country:

At the end of eighties, Albania had a rate of illiteracy of less than 5%, placing it among the developed countries. […] The achievement of universal education must be judged one of the communist regime’s main achievements.

— University of London, [7]

Culture

Gender relations

Antebellum Albania was one of the most reactionary societies on Earth with regards to women’s rights:

For most women, traditional Albanian life was characterized by discrimination and inequality compared with men, reinforced by a wide range of cultural norms. […] In the immediate pre-war period there were just 21 female teachers in the country, a couple of women doctors and no female engineers, agronomists or chemists. Only 2.4 percent of secondary school students were girls.

— University of London, [7]

The Code of Leke (the traditional, antebellum Albanian code of law relating to women) was harshly discriminatory. Even murder of somebody pregnant was punished differently depending on the sex of the fetus that she was carrying:

[T]he dead woman [is] to be opened up, in order to see whether the fetus is a boy or a girl. If it is a boy, the murderer must pay 3 purses [a set amount of local currency] for the woman's blood and 6 purses for the boy’s blood; if it is a girl, aside from the three purses for the murdered woman, 3 purses must also be paid for the female child.

— University of London, [7]

In order to rectify this situation, the PSRA placed an enormous emphasis on women’s rights:

When the communists came to power they considered the emancipation of women as an important political measure, linking it with the destiny of socialism and communism. […] Equality between men and women was stressed continuously and was even included in the Constitution. The Introduction to the Constitution of the PSR of Albania says that “In the unceasing process of the revolution, the Albanian woman won equality in all fields, became a great social force and is advancing towards her complete emancipation." Article 41 of the constitution says: “The woman enjoys equal rights with a man in work, pay, holidays, social security, education, in all social-political activities as well as in the family.”

— University of London, [7]

Women became an active part of the workforce, while previously they had been almost entirely excluded:

Equal rights included amongst others the equal right to have a job. Subsidized day-care nurseries and kindergartens, launderettes and canteens at both workplace, and in residential areas were provided, to make it easier for mothers to work. By 1980 women made up 46% of the economically active population, an increase over one quarter compared with 1960.

— University of London, [7]

Women also made huge advanced in access to education, as well as in positions of government power:

Educational opportunities for women also improved considerably. Table 2.5 shows the increase in the percentage of students who were women graduating from university according to specialties. The table shows that the increase in the percentage during the period 1960-1990, for women engineers was 258.6%, while that for agronomists was 206%, for economists 192%. The same policy was adopted for the participation of women in governing of the country.

— University of London, [7]

According to Edwin E. Jacques, during the Cultural and Ideological Revolution, women were encouraged to take up all jobs, including government posts, which resulted in 40.7% of the People's Councils and 30.4% of the People's Assembly being made up of women, including two women in the Central Committee by 1985. In 1978, 15.1 times as many females attended eight-year schools as had done so in 1938 and 175.7 times as many females attended secondary schools. By 1978, 101.9 times as many women attended higher schools as in 1957.[12]

The PSRA made a number of enormous achievements in terms of gender equality.

Gun control

From 1966 onward Hoxha launched the Cultural and Ideological Revolution. Part of this involved de-professionalizing the armed forces and emphasizing military training. Hoxha claimed during this period that "every Albanian city-dweller or villager has his weapon at home." Jan Myrdal, a Maoist who was given a tour of Albania in the early 70s, likewise reported "the entire Albanian people are armed, have weapons. There are weapons in every village. Ten minutes after the alarm sounds, the entire population of a village must be ready for combat. There has never been any shortage of weapons in Albania, but never have the people been as armed as they are today."[13]

Besides that, by far most resources on Albania do not mention the availability of guns in socialist Albania. Traditionally, many northern Albanians (organized on the basis of tribes) did possess their own weaponry, and there were certainly military drills for the civilian population of the cities from 1966 onward.

Blood feuds

Blood feuds are states of long-standing mutual hostility in which family members or associates take revenge for someone who has been killed or severely disgraced, usually by either killing the person who caused the offense or someone related to them. This in turn would be answered by the family members or associates of the slain offender or their relative, and the cycle continues perpetually. In Albania, this has been a problem for centuries, however under the communist government these were put to a halt through strict punishments; one famous example of these punishments being that the perpetrator of a blood feud would be buried alive in the same coffin as their victim. The fall of socialism in the country precipitated an immediate revival of blood feuds.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 https://theredspectre.com/activity-report-of-the-central-committee-of-the-albanian-labor-party-in-the-parii-congress.html

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/esau-19.pdf#%5B%7B%22num%22%3A229%2C%22gen%22%3A0%7D%2C%7B%22name%22%3A%22Fit%22%7D%5D

- ↑ The Revisionist Alia & Co. — Enemies of the Albanian people (May–July 1991). Roter Morgen.

- ↑ Arjan Gjonga (1998). Mortality Transition in Albania, 1950–1990. London School of Economics and Political Science.

- ↑ Constitution of the People's Socialist Republic of Albania (1976)

- ↑ Portrait of Albania. Available on the Internet Archive.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21

- ↑

- ↑ https://theredspectre.com/against-hoxha.html

- ↑ https://www.google.com/search?tbo=p&tbm=bks&q=taxes+Socialist+Republic+of+Albania

- ↑ Planning in Eastern Europe, Andrew H. Dawson, pages 45-46

- ↑

- ↑ Albania Defiant, 1976, p. 146

- ↑ [1]

Notes

- ↑ Albanian: Republika Popullore Socialiste e Shqipërisë

- ↑ Which would be renamed to the Party of Labor of Albania in 1948.